#1 Possibilia (2014) dir. Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert

[On Cinema] Enter the multiverse… whatever that means 🤷♀️

“An interactive love story set in the multiverse … whatever that means,” is the flippant opening tagline to the Daniels’ 2014 short film Possibilia. For those who haven’t watched it yet, it’s an eight minute film about a couple breaking up delivered in 16 different ways, with the viewer being able to choose how to watch it. A horror film for some, an angsty romantic drama for most others, Possibilia is a film whose form is greater than its content — focused on our desire to choose and challenges the boundaries of audience participation.

If you’d like to follow along, watch it for free on eko.

Maybe by now you’ve heard of the Daniels (director duo Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert) and their film Everything, Everywhere, All At Once (2022). If you haven’t, you’re probably not a cult follower of A24 or close friends with Asian Americans (fair enough), but tldr; it’s a sci-fi action comedy film about a middle-aged Chinese immigrant woman who journeys through the multiverse to save her daughter from destroying it.

When I was deciding what to cover first on the silly bus, I probed around the contemporary trends I was seeing in (American) cinema that I wanted to drill away at. What social anxieties do these trends try to respond to or assuage? I landed on the multiverse, a concept that was suddenly the perfect storytelling structure to invigorate audiences who were used to the old tricks. A blend of anxiety-ridden science fiction, linear plot boredom, and reimagining what-could-have-been alternative worlds, the multiverse seemed infused with the same ethos of why people write fanfiction.

First popularized in mainstream and commercial cinema by the Marvel Cinematic Universe (The Amazing Spider-Man, Doctor Strange, etc.), the multiverse is a theory that multiple universes exist at the same time. It champions the idea of multiplicity instead of singularity. It suggests that at every point of time a character comes to make a decision, they make a fork in that universe. Theoretically, you are not one person in the present, an aggregate of all your choices; but you exist in multiple spaces and times.

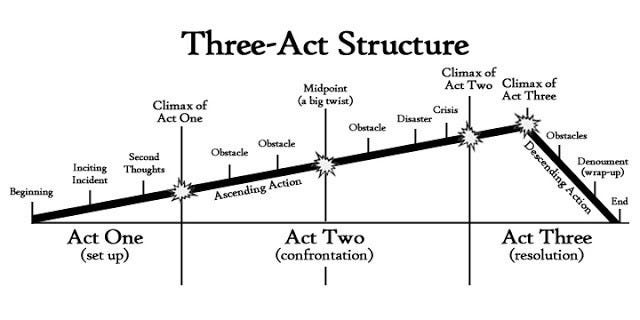

Beyond its scientific origins, the multiverse is both a money-making scheme (hence why the MCU kills off and brings back popular characters and recycles plot like plastic) and it’s been a way of revamping Western storytelling that famously, as Diane Lefer puts it, traces a narrative arc like a male orgasm.

While presented as groundbreakingly novel, sci-fi, and futuristic, this theory of the multiverse and its cinematic applications aren’t exactly new. Just commercially packaged and mass consumed. We might have always been thinking about it subconsciously, us being fickle, pensive human beings who believe that choosing differently may have made us an entirely different person. After every major life decision, don’t you wonder, What if I had chosen something else?

Zeroing in on specificity, this multi-world and multi-variable imagining may be more omnipresent for certain others. It acknowledges that conditions of living would have been better if it had not been for x, y, z variable that we do not have. Some storytellers question these circular trans-spatial, cross-temporal stories all the time like, What would life be like if I hadn’t left the country? If I hadn’t learned this language? If I had a job like X? Went to university like Y?

In their early flirtations with the multiverse, the Daniels wrote and directed a short film called Possibilia, which debuted in 2014. It wasn’t just any short film, but an interactive short film first pitched to the directors by XBOX Entertainment (yes, a video game company), and in collaboration with interactive storytelling platform Interlude (now rebranded as eko). Possibilia was the perfect marriage of new technology, storytelling, and distribution of virtual reality (VR) cinema.

In the Daniels’ case for Possibilia, they explore the multiverse in a macro-generalizable sense. It’s a relationship break-up. The perfect place to wonder about the different roads each person could have taken, how the relationship could have been salvaged, but didn’t. The feelings after a break-up are messy and contradictory; you’re left wondering what exactly happened and where exactly was the wrong turn. This short film creates the technological infrastructure for you to imagine and map out every possibility that you could.

This choose-your-own-adventure storytelling technique is probably familiar. Maybe you’ve encountered them in your childhood with the original book series, or maybe it was more recent, when Netflix released their first interactive episode Black Mirror: Bandersnatch (2018). The Daniels were thrilled to make an interactive film because it was a chance to make movies more like video games, an experiment that had never been successful before in longer form videos.

The short film begins with a white couple (Zoe Jarman as Pollie and Alex Karpovsky as Rick) arguing at the kitchen table. The dialogue is generic, it had to be for the interactivity to work, noted the directors. Suddenly, the screen splits, the characters double into two separate scenes, and the dialogue criss-cross over each other. You enter the multiverse.

The screen instructs the viewer to click the arrows or press the keyboard arrows to navigate the scene. Very cool. This is not your average film; it’s a simulation in which you’re supposed to participate and propel the outcome. It’s both the multiverse, a catalog of 16 different scenarios that are equally real, but it’s also up to the viewer to control which one(s). As a viewer, I flip-flopped between the two scenes.

At one point, Pollie says the fatal words, “What I am in the moment isn’t going to change.” Like a magic phrase, two scenarios multiply into four. There’s one of the couple talking in the laundry room very close to each other. They’re saying the same dialogue as every other scene, “I need to to something drastic,” but in this one they’re breathy and horny — the couple sneaks in neck kisses in between their pissed-off-desperation. If you click the arrow to the right, you might see the couple arguing next to the staircase. Pollie is angry; she yells, “I need to to something drastic,” while flinging picture frames off the walls. It’s a full-blown tantrum.

Then, the number of scenes multiplies into eight. The dialogue has de-escalated from fighting. In one scene, Pollie smokes a cig outside. In another, they’re arguing outside in the garden. Then before you know it, the number of scenes multiplies into 16. It’s almost symphonic, where the dialogue merges into one, but the choices of scenarios expands like an accordion. I’m dizzy with whiplash, trying to look at every one.

Without warning, all sixteen scenarios shrink back into two. The characters walk into anticipated frozen images of themselves, before the film collapses back into one scene.

What’s different in Possibilia, because of its interactivity, from the Marvel movies or other multiverse-theorizing fiction is that the multiverse is left unexplained. There’s no omniscient narrator explaining why there are 16 versions of the same couple on a split screen, there’s no Star-Wars-title-scroll to explain that the multiple couples on the screen is just another version of the original; it’s not like the scenarios show the couple on another planet. It’s pretty much self-explanatory. The multiverse is not meant to build words by any means; here, it just mirrors and feeds off the nontraditional storytelling form of what it means to break up.

For the last compressed scene, Rick and Pollie are sitting back at the kitchen table. In classic short story fashion, we return back where we started in the beginning, but somewhat in a changed, journeyed way. They’re sitting back down, calmly and cathartic, after minutes of distressed fighting. The tone of the ending, whether it feels like the characters are at closure, or resigned and given-up, depends on which scenarios the audience has chosen to follow. Rick wonders if the two of them are better off having been in the relationship together. Pollie sagely says that isn’t that what a relationship is? Not being able to recognize whether or not you’ve changed for the better or for the worse? Forgoing the “or,” Pollie suggests that a relationship, in its totality, is a way to “recognize the gestalt of it all.”

Now I haven’t heard the word “gestalt” used by an actual person besides a Psychology textbook. Rick in the film doesn’t know what the word is either, but understands the gist of what she’s saying, that the relationship as a whole is different from the sum of its parts. This is where the ideological part of the short film comes in, where the directors tell the viewers what to think about the chaotic 16 scenarios. To contextualize, I’m going to ring in one of the greatest proverbs of art written by Vivian Gornick: “the way the narrator sees things is the thing being seen.”

In each of the scenarios, we see how the couple deals with conflict, we see how they interact with each other, how they love each other; and largely, who they are as individuals. In Pollie’s dialogue, the directors suggest how we’re supposed to interpret this multiplicity alongside the singularity we revert back to. The relationship is a simultaneous existence of ands: it’s toxic and it’s violent and it’s loving and it’s caring and it’s failing to communicate and it’s failing to hide. The relationship, and the multiverse, is contradictory. As viewers, we may be able to choose how we want to see the delivery of the break-up — outdoors, angry on a staircase, desperate in the laundry room — but it doesn’t change the fact that the film, in the end, is just a holistic picture of their relationship. It’s not necessarily flattening in a bad way, but it’s like an optical illusion, that the whole is perceived differently.

In an article for Wired, Shanti Escalante-de Mattei says:

The multiverse narrative […] is one that ultimately strives toward wholeness. Though fragmentation has to first be acknowledged and even celebrated, jumping between worlds and selves isn’t a sustainable state.

The gestalt principles seem to be an apt way of articulating the point of the multiverse. That the wholeness, that the short film reverbs back to, is different from the multiplicities of the couple. The multiverse narrative exists, of course, with limitations. It offers a cursory glance of some possibilities, while anchoring itself in a motion that still has to be continuous. And fragmentation isn’t continuous, wholeness is.

As technological platforms advance and interest in transforming the “passivity” of the viewer — and perhaps the smallness of the human in the digital age — increases, we also must interrogate the choices that are presented as choices. The choices are expected to lead to somewhere different. But do these choices become ways to prime viewers to accept and stop questioning the ending we’re given by the filmmakers because we have “chosen” it?

I wonder why these interactive films aren’t more popular and mainstream, especially when there is already the technology to create them. The directors point out that the filming and writing process was much more arduous, having to retake and synchronize the timing so meticulously. So there’s a production and investment reason there. But I wonder if viewers even want to be able to choose their own ending. Aren’t stories told and not chosen? Isn’t the most “active” a viewer can become to rebel against the story they’re told and to create their own?

In the final moments of the film — if you can call it a conclusion because the film never really ends — Rick asks, “What if you stayed for a second?” Pollie is just about to leave when the screen splits into two again. Once more, the loop begins from the start. Differently though, like listening to the same song in a movie but at a different point in time. It gives an uncanny feeling. Maybe we can think about Freud’s concept of repetition compulsion, “the desire to return to an earlier state of things.” I’m confused about what we’re returning to. The relationship is supposed to be expansive, multiplying, reproductive, limitless in the multiverse. It’s strange, though. Shouldn’t this realization that there are whole worlds and universes out there, ones that we have never experienced, feel freeing? Shouldn’t the viewers’ knowledge of and partaking in choice make us feel more in control?

Instead, when the loop begins again, I feel like I’m running on a hamster wheel. Sure, I can move my neck and glance to the side. The world is very expansive horizontally. I’m not too convinced my choices in the short film led me anywhere, though.

Additional readings xoxo:

Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life” (1998)

Daniels’ Everything, Everywhere, All At Once (2022)

16 Ways to Leave Your Lover: Watch Daniels’ “Possibilia,” a Choose-Your-Own-Break-Up Interactive Movie by Carlos Aguilar (2016)

Why the ‘Multiverse’ Rules Cinema by Abigail Nussbaum (2022)

The Internet Gave Rise to the Modern Multiverse Movie by Shanti Escalante-de Mattei (2022)

The multiverse, what a money-making scheme.. :)